The Praise Paradox: How Much is Too Much?

The words we use at the dinner table carry weight. More than just encouraging action, they can have a lasting impact. But is there such

If you offered your teen one chocolate bar now, or two bars in a month’s time, which would they pick?

We know the answer. They’d take the one bar now. It’s not because they’re bad at maths; it’s because humans are wired for “NOW.” In psychology, they call this Hyperbolic Discounting. The further away a reward is, the less it’s worth to our brains.

This is the exact wall parents hit when they try to motivate teens with talk of “university places,” “future careers,” or even “summer exams.” To a teenager, those things are so far away they feel invisible.

Brain scans show that when teens think about their future selves, their brains react as if they are thinking about a complete stranger. You aren’t asking them to study for themselves; you’re asking them to study for a person they don’t even know yet.

The Study: UCLA psychologist Hal Hershfield used fMRI brain scans to see how we perceive ourselves over time.

The Discovery: He found that for many people, the brain’s activity when thinking about their “future self” looks remarkably similar to when they think about a complete stranger.

The Teen Twist: In teenagers, this gap is even wider. Because the prefrontal cortex (the part of the brain responsible for long-term planning) is still developing, the “Future Me” who takes the exams in May feels like a totally different person than the “Current Me” who wants to play Fortnite today.

The Result: When you ask a teen to revise for their future, their brain treats it like a request to do a huge favour for a stranger. Most of us wouldn’t give up our Friday night to help a stranger move house—and teens feel the same way about studying for their “future self.”

Source: Hershfield, H. E. (2011). “Future self-continuity: How conceptions of the future self transform intertemporal choice.”

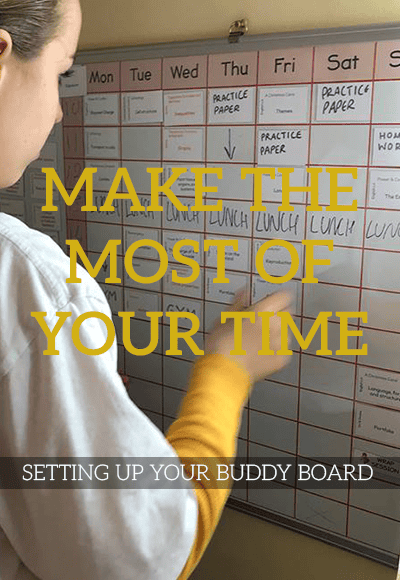

To get a teen to engage in revision planning, we have to move the goalposts closer. We need to stop selling the “Career” and start selling the “Weekend.”

At The Study Buddy, we suggest reframing success. Don’t look at the GCSEs in June. Look at the end of this week.

The Goal: Just do slightly more than you did last week. Or not get nagged. Pick something achievable that feels like success. The dopamine hit of achievement is key.

The Payback: By picking something achievable, your teen will get that feeling of success. The dopamine hit of achievement is key and will spur them on to do it again, and again, and again!

By shortening the timeframe, the reward suddenly has value again. Revision stops being a mountain they have to climb for a stranger, and becomes a series of small steps they take for their own [more immediate] benefit.

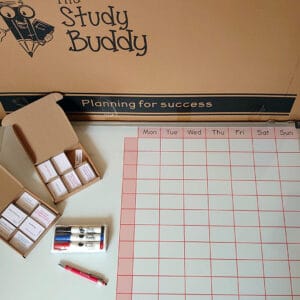

Our GCSE Special bundle is everything you need to get going quickly and easily.

The words we use at the dinner table carry weight. More than just encouraging action, they can have a lasting impact. But is there such

You can’t out-supplement a bad diet, but you can certainly optimize a good one. From the sleep-restoring power of Iron to the brain-boosting benefits of

If your teen’s revision plan didn’t quite survive half-term, you aren’t alone. But dwelling on a “failed” week is the fastest way to derail the

An offer code will be sent to you. By subscribing to our newsletter you agree to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Thank you for signing up! Check your inbox soon for special offers from us.

In the meantime, you can use the code Welcome5