“There’s Loads of Time” (And Other Sunday Night Myths)

Ever wonder why “it’ll only take ten minutes” turns into a three-hour Sunday night meltdown? It’s not laziness—it’s biology. We explore the Planning Fallacy and

We’ve all been there. It’s 8:00 PM on a Sunday. You ask about the History essay. They say, “It’s fine, I’ll do it in a bit, it’s only a few pages.” By 10:00 PM, the printer’s jammed, they’ve barely started, and there are tears (they might be yours!) As a parent, it feels like they were lying to you. But here’s the kicker: They were actually lying to themselves.

In 1994, psychologist Roger Buehler conducted a study that should be required reading for every parent of a GCSE student. He asked students to estimate when they would finish their thesis:

The “Realistic” Guess: Students thought they’d finish in 34 days.

The “Worst Case” Guess: They thought it would take 49 days, tops.

The Reality: It actually took them an average of 55 days.

Even when they tried to imagine things going wrong, they were still too optimistic. This is the Planning Fallacy. Our brains are hardwired to ignore our past failures and assume that “this time” will be the perfect run.

Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman explains that when teens plan, they take the Inside View. They look only at the task in front of them and their current energy levels.

They ignore the Outside View—the data that says “Last time I did this, I got a snack three times, my phone buzzed twice, and I spent ten minutes looking for a highlighter.”

His book, Thinking, Fast and Slow is a great read for understanding more about how we think.

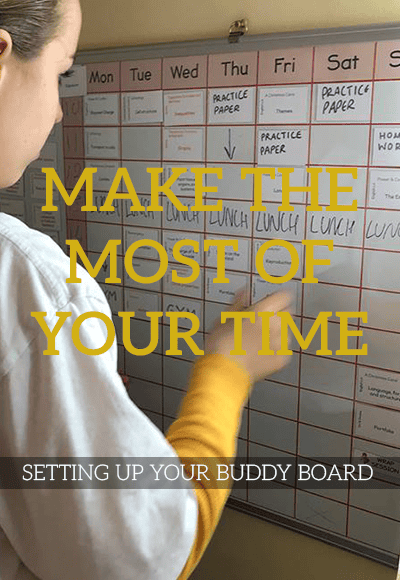

This is one of the many areas where The Study Buddy’s approach excels. In our proposed weekly review and plan (WRAP); you aren’t “checking up” on them; you’re acting as their External Data Source.

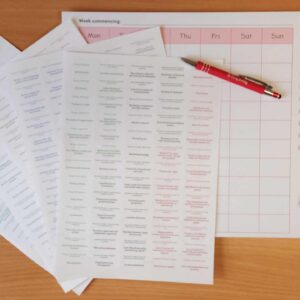

1. The “Buffer” Rule (The 50% Tax) Instead of arguing about how long a task takes, agree on a “Science-Based Buffer.” If they think a practice paper takes 30 minutes, the plan should allocate 45. If they finish early? That’s “Profit Time”. (Take a look at last week’s article on time

2. Focus on “Units” not “Tasks” “History Revision” is a mountain. “One 20-minute mind map on the Cold War” is a unit. It’s much harder for the Planning Fallacy to ruin a 20-minute window than a 3-hour one.

3. The “Post-Game” Analysis At the end of the week, look at the plan together. Not to tell them off for what they didn’t do, but to ask: “Which tasks took longer than the brain guessed?” This builds their “Outside View” for next week.

The Sunday night meltdown isn’t a parenting failure; it’s a biological mismatch. Your teen’s brain is optimistic, dopamine-seeking, and views their future self as a stranger. You can’t argue with biology, but you can outsmart it.

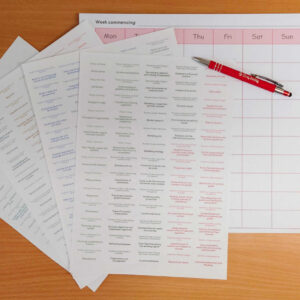

At The Study Buddy, we suggest replacing the emotional “Why haven’t you started?” conversation with a rational, 30-minute WRAP (Weekly Review And Plan) session, planned for the end of each week. Think of it as your Sunday night stress-repellent.

By sitting down for just half an hour to review the week, you move from Drama (emotional guesses and missed deadlines) to Data (realistic time blocks and built-in buffers). It’s the moment where you apply the “Planning Fallacy Tax” and agree on the “Profit Time” for the coming week. When the plan is on paper, you stop being the “nagger” and start being a coach.

In this way, you aren’t fighting your teen; you’re both just working the system to ensure that they reach their full potential.

Our GCSE Special bundle is everything you need to get going quickly and easily.

Ever wonder why “it’ll only take ten minutes” turns into a three-hour Sunday night meltdown? It’s not laziness—it’s biology. We explore the Planning Fallacy and

One sweet now or two sweets in a month? Discover how the concept of Future Self might be skewing your teens perception of value and

Is your teen’s revision actually sticking? Discover the Dunlosky study findings on high-utility techniques like Spacing and Interleaving. Learn how to beat the Forgetting Curve

An offer code will be sent to you. By subscribing to our newsletter you agree to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Thank you for signing up! Check your inbox soon for special offers from us.

In the meantime, you can use the code Welcome5