Don’t look back in anger

Why does the perfect, colour-coded revision schedule you made for your teen ends up in the bin by Tuesday? It’s not a lack of gratitude—it’s

As a parent, seeing your teen at their desk with a highlighter in hand is a relief. It looks like progress. But according to a massive study led by Professor John Dunlosky, that highlighter might be doing more for the stationery industry than it is for your teen’s GCSE grades.

With mock exams looming, this is the perfect time to look at the Dunlosky (2013) study. It’s the “Gold Standard” of revision research and, honestly, a bit of a wake-up call for many students.

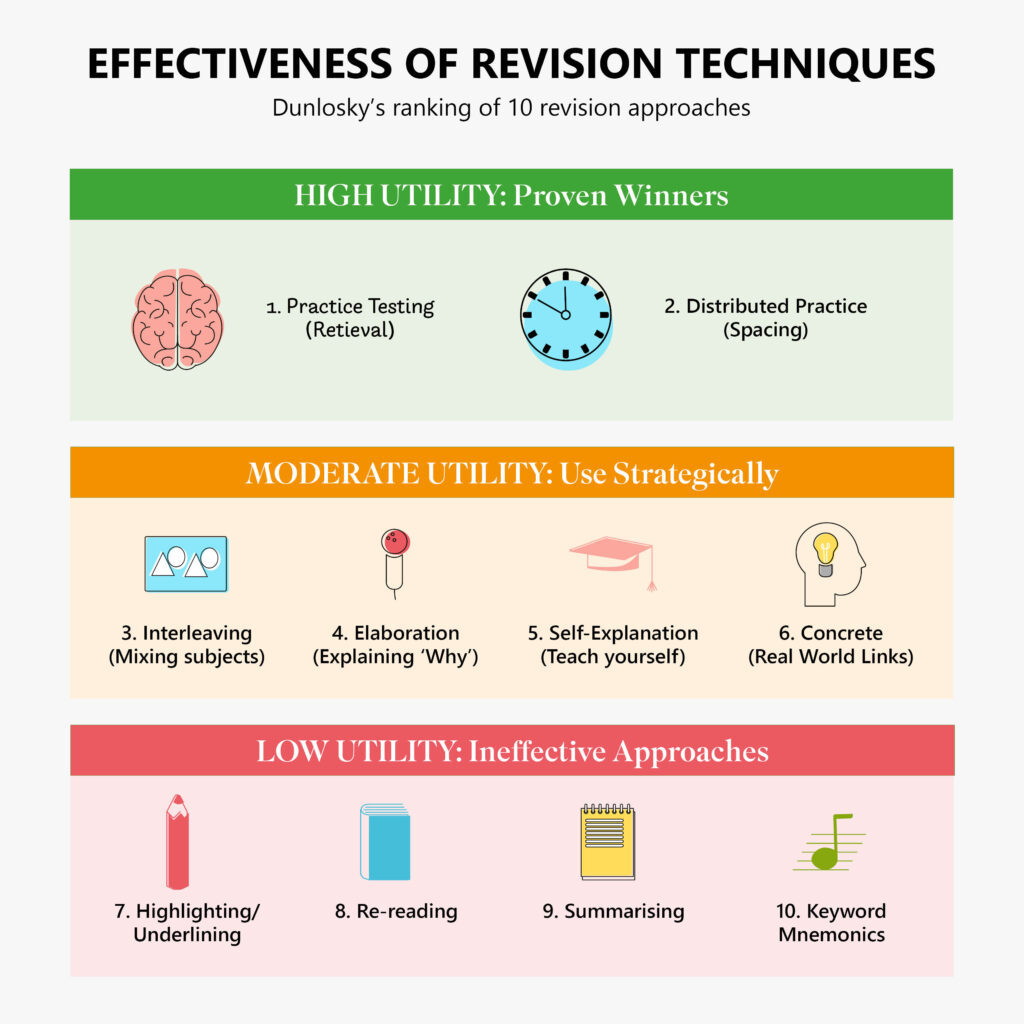

Dunlosky and his team reviewed 10 common revision techniques and ranked them by “Utility” (how much “bang for your buck” you get). The results are often surprising because the techniques students love most (like highlighting) are often the least effective.

To understand why some revision fails, we have to look at how information moves from a book to the brain.

When a student rereads a chapter or highlights a sentence, they are engaging their working memory. Because the information is right there in front of them, it feels “fluent.” It’s easy to read, so the brain whispers, “I’ve got this. I know this.”

This is the Illusion of Learning.

The student isn’t actually learning; they are simply becoming familiar with the text. The information is sitting in their short-term “working” memory, but it hasn’t been anchored into their long-term memory. As soon as they close the book, the “fluency” disappears, and on exam day, they find they can’t actually recall the facts.

Dunlosky’s research labelled Highlighting, Rereading, and Summarising as Low Utility.

They are passive. They don’t force the brain to do any heavy lifting. If the brain isn’t challenged to retrieve the information, it assumes the information isn’t important enough to keep.

To understand why some revision sticks while other sessions are a waste of time, we have to look at the Forgetting Curve.

When a student learns something new, their memory of it is at 100%. However, without intervention, that knowledge begins to drop off almost immediately. By the next day, they may only remember 50%. By the end of the week? It’s often gone. The answer is to call on information from our long-term memory in the form or rehearsal or retrieval.

The study found two techniques that consistently outperform the rest. The common thread? They both move beyond the working memory.

This is the act of reaching into the brain to pull information out. Whether it’s a past paper, a flashcard, or just a blank sheet of paper, the “struggle” to remember is what signals the brain to store that data permanently.

The Rule: If it feels hard, it’s probably working.

Research shows that study spread over five days is vastly superior to a five-hour “cram” session. Spacing forces the brain to “re-learn” the material just as it starts to fade, which doubles the strength of the memory.

In the Dunlosky study, Interleaving was highlighted as a powerful way to build deeper understanding. Most students study in “blocks”—an hour of Algebra followed by an hour of Fractions.

While blocking feels easier, it often leads to a false sense of security. Because the student is doing the same type of task repeatedly, the “method” stays in their working memory. They aren’t learning how to solve the problem; they are just repeating the last step they took.

Interleaving is the strategy of mixing different types of problems or topics within a single session. Instead of 10 Algebra questions, do two Algebra, then two Geometry, then two Fractions.

This constant “switching” forces the brain to actively discriminate between concepts. It’s harder, and it takes longer, but it ensures that the knowledge is anchored by meaning, not just repetition.

In his research, Retrieval Practice and Distributed Practice (Spacing) were given a “High Utility” rating; Interleaving was actually given a “Moderate Utility” rating. The “Moderate” rating was simply because, at the time of the study, there was less evidence of it working across every single subject (like learning a language or history) compared to the “universal” power of spacing and testing.

This is exactly why we designed our system with physical magnets.

The Board allows students to visually Interleave their subjects, ensuring they aren’t just stuck on one topic for hours.

The Magnets allow for Spaced Practice. By moving a “Trigonometry” magnet to three different days across a fortnight, the student is systematically beating the Forgetting Curve rather than fighting against it.

Swap the Highlighter for a Pen: Instead of highlighting a chapter, ask your teen to close the book and write down the 5 most important things they just read.

The “Study Buddy” Advantage: This is exactly why our system uses physical magnets. It forces students to distribute their subjects across the week (Spacing) and creates a clear structure for testing themselves on specific topics (Retrieval).

It is easy to feel like a bystander during mock exam season—watching the highlighters come out, and the stress levels rise. But understanding the science of the Forgetting Curve and the Illusion of Learning changes your role from “nagger” to “coach.”

Remember, if your teen is finding it hard to switch between subjects or is frustrated that they can’t remember a fact immediately, that is actually a good thing. That mental effort is the sound of the “working memory” handing the baton over to the “long-term memory.”

You don’t need to be an expert in Pythagoras’ Theorem or the causes of the Industrial Revolution to help them succeed. You just need to help them clear the clutter. By encouraging them to Space their sessions, Interleave their topics, and prioritise Retrieval over rereading, you are giving them the most valuable tool of all: an effective brain.

So, take a breath. Put the kettle on. Remind them that it’s not about how many hours they sit at the desk, but how they use them. With the right plan on the board and a bit of science in their pocket, they’ve got this—and so do you.

Swap the Highlighter for a Pen: Instead of highlighting a chapter, ask your teen to close the book and write down the 5 most important things they just read.

The “Study Buddy” Advantage: This is exactly why our system uses physical magnets. It forces students to distribute their subjects across the week (Spacing) and creates a clear structure for testing themselves on specific topics (Retrieval).

Our GCSE Special bundle is everything you need to get going quickly and easily.

Why does the perfect, colour-coded revision schedule you made for your teen ends up in the bin by Tuesday? It’s not a lack of gratitude—it’s

Approaching the subject of revision over half-term can be a tight-rope walk. Encouraging and persuading while being careful not to tip into nagging. In this

The Sunday Night Standoff is optional. Move from “Drill Sergeant” to “Project Manager” with our downloadable WRAP Agreement. Featuring the “No-Nag Clause” and “Profit Time,”

An offer code will be sent to you. By subscribing to our newsletter you agree to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Thank you for signing up! Check your inbox soon for special offers from us.

In the meantime, you can use the code Welcome5